Demons and “Vague Hearsay”

Imagine arriving somewhere new and meeting a bunch of new people. As everywhere, some bore you, and others interest you. If you’re lucky, there may be a few you like immediately. And yet all of these people won’t shut up about yet another person whom you have not met or even seen. Opinions on him (or her) are divided: some adore him, others despise him, but no one is lukewarm about him. From everyone, you hear a new, strong, and idiosyncratic opinion. Can you imagine experiencing, this, hearing such disparate things from disparate people, and *not* be burning with excitement to see this person for yourself, and form your own opinions about him? This is the sort of mystique that Dostoevsky builds around Nikolai Vsevolodovich Stavrogin, the central character of his great quasi-political farce-tragedy Demons.

Every single character of Demons is directly related to the character of the confident, handsome, mysterious Stavrogin. His mother, Varvara Petrovna, and former tutor, Stepan Trofimovich, are centerstage throughout the novel, and remain some of Dostoevsky’s greatest character-creations. The novel’s young women are all Stavrogin’s romantic options, the novel’s young men, Stavrogin’s disciples. When reading Demons, one feels that most of the bizarre things that happen could never have happened without Stavrogin’s influence. A powerful aura surrounds him; his natural confidence inspires all those around him to act boldly. And yet Dostoevsky’s depiction of Stavrogin is almost opposite to what he normally does with his central figures.

Ordinarily, Dostoevsky will place his readers deep inside his character’s minds, spending 20 or 30 pages at a time familiarizing us with their desires, motives, and fears.

By the end of these passages, we almost feel like we know everything about a character, and all too often, we end up caring deeply for them and wanting to see them happy or well. This is how Dostoevsky treats all the other central characters of Demons, especially Varvara Petrovna and Stepan Trofimovich, the novel’s matriarach and patriarch. It is one of Dostoevsky’s key gifts as a novelist and part of the reason he is called the world’s greatest psychologist. It should never be forgotten how much Freud loved and learned from Dostoevsky, considering The Brothers Karamazov the pinnacle of literary art, right beside Hamlet and Oedipus Rex.

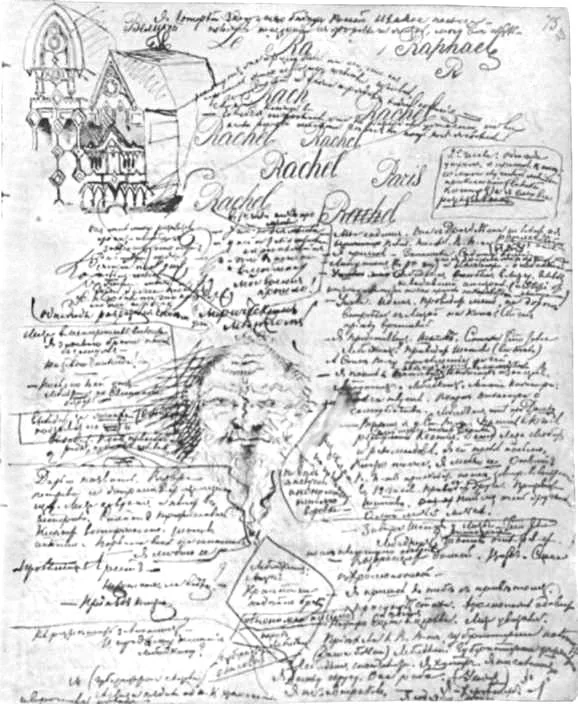

A page of notes about Demons that Dostoevsky scribbled down. Dostoevsky loved doodles and often included them in his notes

But as deeply as we get to know his mother, his childhood tutor, his various romantic options, and his friends and co-conspirators, Nikolai Stavrogin always feels remote and inscrutable to us: we never know what is going on in his head. Most of what we know about him seems to come through “vague hearsay.” He is tall, handsome, and strong, and with his natural dignity, and odd willfulness, he captivates the entire town, and by extension, the reader. He also possesses incredible self-control, and tows the line carefully between pleasing attributes, without excess: “He was not very talkative, was elegant without exquisiteness, surprisingly modest, and at the same time bold and confident like no one else.” (43).

And yet, these glimpses of what others think about Stavrogin, don’t necessarily represent all we know about him. Dostoevsky wrote another chapter that was so lurid it ended up cut from the final version of the novel. Called “At Tikhon’s,” it is one of those classic Dostoevsky episodes where a character has a conversation at someone else, and this time the monologist is Stavrogin. The listener is the respected monk Tikhon, whose advice (or simply listening ear) Stavrogin has sought out. The chapter contains such sensational details about Stavrogin’s past that it reads like a gossip column (making for great reading!), emphasizing, as Dostoevsky does elsewhere in the novel, Stavrogin’s superhuman self-control in most respects, and his moments of bizarre capriciousness in others. After mentioning such lurid details as how he stopped masturbating at the age of seventeen, at “the moment I decided I wanted to . . . I am always master of myself when I want to be.” (p. 693), he then proceeds to recount an awful deed of his life that still haunts him. Years ago, he was staying at the house of a family that had a fourteen-year-old daughter, whom he rapes, and who then hangs herself from shame. Stavrogin is simultaneously torn up by guilt and elated by a strange, infernal pride in this monstrous act. As he puts it, he was animated by an “intoxication of the awareness of the depth of my meanness. It was not meanness that I loved (here my reason was completely sound) but I liked the intoxication from the tormenting awareness of my baseness.” (693).

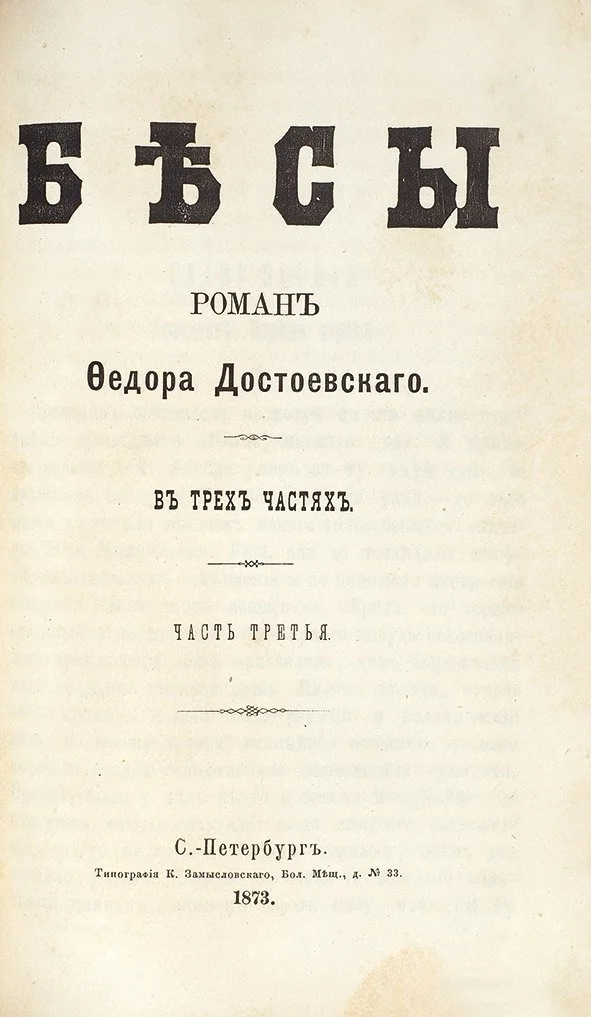

The title page (in Russian) to the first 1873 edition of Dostoevsky’s Demons, which was previously published under the name “The Possessed.”

This chapter, which is initial editors suppressed (for obvious reasons), is almost always included in modern editions of the novel, but usually as an appendix, rather than part of the main text. It serves an interesting purpose, helping to explain the mysterious character of Stavrogin, and I cannot imagine rereading the novel without the awareness of what I learned about him from this other chapter. And yet this appendix is not technically “part” of the novel as we have it.

This presents many interesting questions. If understanding Demons depends on understanding Nikolai Stavrogin, the epicenter of the novel, what part does the suppressed chapter “At Tikhon’s” play in our minds? Can I reread the entire novel, and unlearn what I learned “At Tikhon’s?” How much weight does this chapter hold? Is it canon?

When reading a chapter like this, one asks “if it did not show up in the final novel, did it actually happen this way?” It immediately occupies a nebulous medial position in the reader’s minds, not part of the novel, but not not part of the novel either. It has the distinction of being penned by the author but the discredit of not making into Demons’ final version. Its reliability is somewhere between absolute canon (as if it were a part of the novel), and discarded material that didn’t make the final cut. Because of its confusing medial position, I argue that it almost resembles rumor or hearsay.

The editorial flourish of including “At Tikhon’s,” Stavrogin’s most personal episode, as an appendix to most editions of Demons, amplifies the unique way in which Dostoevsky chose to present Stavrogin. Dostoevsky chose to present Stavrogin as a very mysterious character, and so much of what the reader discovers about the character is from rumor and hearsay around the town.

A rumor gains a certain importance just by existing and being propagated. It’s being spoken or shared imbues it with a certain weight. An importance that is not the same as sheer fact, to be sure, but nevertheless, isn’t meaningless or worthless. And yet, if it remains a rumor that is neither confirmed nor disproven, it never becomes a fact, it just stays a possibility of something that may be true. And the chapter “At Tikhon’s” will always occupy this medial position. Demons was published and gained respect and admiration without this suppressed chapter, and thus it will never be as important as the rest of the book. And yet it has a weight and importance of its own, in that it sheds light on the mysterious central character of Demons, Nikolai Stavrogin.

In yet another way, At Tikhon’s resembles rumor or hearsay. In addition to occupying that curious medial position in between pure canon and undeniable apocrypha, the sensationalism of its revelations makes it feel like a rumor in and of itself. “At Tikhon’s” contains exactly the sort of information that would be chocked up as rumor anyway, facts that people close to the guilty party would want to suppress, and facts that enemies of the guilty party would share widely, though in hushed voices.

And for those to whom, the author’s original intentions are always absolute and must be obeyed and respected, Dostoevsky makes a poor example. It should not be forgotten that an editor rescued Crime and Punishment from Dostoevsky himself, who had included dozens of sermonizing, endlessly didactic pages of Christian apologetics and ethics, which the editor wisely discarded. Crime and Punishment could have been a terrible (and banal) little Christian tract, rather, than the extremely special grim novel that the editors wisely saw that it could be, and ended up being. Only very rarely is a novel the work of only the author. Many hands, many persons, are involved.