Apollo’s Timelessness

Igor Stravinsky constantly reinvented himself, creating a incredibly varied corpus in which almost every piece presents something new and special . But one piece, his 1928 ballet Apollo, still seems startlingly divergent from the rest of his little masterpieces. Stravinsky sets Apollo (sometimes called Apollon musagète, or “Apollo Leader of the Muses”) for a simple orchestra of just strings, avoiding harsh dissonances and in fact anything with an “edge” to it. This was a completely unexpected move from the composer who had made his name with The Rite of Spring, a work driven by its winds and brass, filled with jarring dissonances and crisp, “biting” articulations. Even among the comparatively “tame” works of his neoclassical period, Apollo represents an extreme. Pulcinella, Symphony of Psalms, the Octet, Mavra, The Rake’s Progress, the Violin Concerto, none of these have anything approaching Apollo’s clarity, serenity, and almost ethereal purity.

Whenever I listen to any programmatic music, I like to consider the ways in which the composer uses music, an abstract art form, to portray the extra-musical plot. How does he express these things musically? How does he communicate these plot points to an audience? Apollo presents an interesting problem, for there is essentially no plot, another one of the work’s eccentricities, Set in the Greek Golden Age, the ballet depicts the birth of Apollo, his instruction of three out of the nine muses in their respective arts, and ends with their ambiguous “apotheosis.”

Stravinsky’s neoclassical music is filled with references to earlier music. But returning to Apollo recently, I was overwhelmed by the sheer variety and number of these historical reference points, as well as how frequently Stravinsky switches between them. I had always thought of Apollo as principally neo-Baroque, owing most of its heart to Bach and French 18th century music, like Rameau. But I found that this represents only a part of a much more complex story.

The work’s neo-baroque elements, though overemphasized by critics, are certainly an important part of the equation. Apollo’s theme contains double dotting characteristic of the French overture style. “Apollo’s Variation,” an important episode early in the ballet, begins with a clear nod to Bach’s solo violin works. And yet much of the rest of the work seems born of later music.

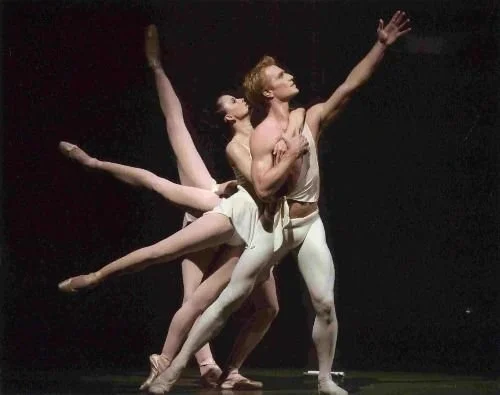

An image from a recent production of Contemporary New York City’s Ballet production of Stravinsky’s Apollo. All white costumes highlight the relative “purity” of the music.

The world of nineteenth century (yes, nineteenth century) ballet pervades so much of this piece: I hear it especially in the latter half of the “Birth of Apollo” and in the muse variations. Tchaikovsky and Delibes cast a large shadow on the world of ballet, but it was a shadow that prior to this Stravinsky had consciously avoided. Think of the three early ballets, and Les Noces. Are Tchaikovsky and Delibes explicit in this music? Decidedly not. It almost appears that Stravinsky was trying to avoid these influences in those works. Even The Firebird seems to owe more to Rimsky-Korsakov’s fairy-tale operas than to Sleeping Beauty or The Nutcracker. But in Apollo and shortly after, La Baiser de la fee, Tchaikovsky and Delibes return in full force in his music.

Many of Apollo’s harmonies feel like the quasi-French ones borrowed from pop music. I don’t hear Ravel or Poulenc in this music, but the harmonies and suspensions, color chords, and blue notes that those two took from popular music are everywhere in Apollo.

And yet despite all this, if I had to assign a specific “decade reference” to much of this music, it would not be the age of Bach, Rameau, Delibes, Tchaikovsky or Poulenc, but decidedly nineteenth century, possibly 1810s or 1830s. I sometimes think that if any of the great bel canto composers, especially Rossini or Bellini, were to write a ballet for just strings, much of it would resemble this, Stravinskyisms aside. Apollo’s long Italianate melodies certainly owe something to Bel Canto music. Bellini seems to me the dominant figure, with his focus on a serene mood, even in moments of high emotion; his (relative) avoidance of secondary dominant harmonies; and his emphasis on “musical line” above all.

Of course, one should bear in mind that I’m speaking comparatively. Think, “Apollo among Stravinsky’s oeuvre,” or “Apollo among the great music of the 1920s”. A first-time listener might not hear any serenity in this music, especially if they don’t know Stravinsky’s other music very well. As an aside, I imagine that Bach and Bellini would be shocked by the relative “chaos” of Apollo, although they would also prefer this piece to most everything else written about the same time.

In my most recent study of the piece, the number of references to music of different eras made a huge impression on me. I came to conclude that Stravinsky wanted to give the piece a sense of coming from the past but did not want a single bygone era to dominate the mood. The sense for the listener is a grand sense of nostalgia but for different little “golden ages” in music history. At one moment the music of Bach is evoked, but only moments later Delibes makes an appearance, before resolving on a chord reminiscent of the popular music of the 1910s. The listener is left nostalgic for bygone periods of music history, without being able to identify precisely what periods he is thinking of. The listener perceives a certain “timelessness,” a timelessness characteristic of the Greek Golden Age. This is an extraordinary effect, and part of Apollo’s wonderful magic.

The Golden Age, as the Greeks thought it, is the rough Judeo-Christian equivalent of Eden before the Fall. For the Greek imagination, this period consisted of a time of widespread nobility, innocence and virtue, and its end coincided with Prometheus’s theft of fire and the gods’ revenge, Pandora’s box. As Hesiod put it: “[Men] lived like gods without sorrow of heart, remote and free from toil and grief: miserable age rested not on them; but with legs and arms never failing they made merry with feasting beyond the reach of all devils.” In Western thought, this period is often depicted quite pastorally, a time before many ancient inventions, but in which they were not needed. Before responsibility, before agriculture and its tending, what use is timekeeping? When one keeps the work’s Golden Age setting in mind, Apollo’s difficulties suddenly seem to click.

Robert Sanderson’s oil painting of Apollo dancing with the nine muses. Apollo is distinguished by his quiver and bow, whereas each of the muses is identified by her name in Greek beneath each dancing figure. While Sanderson, a now little-known figure, painted mostly images of everyday life, he turns to a mythic setting for this study, a colorful recreation of Baldassare’s Peruzzi’s Renaissance engraving.

For one thing, its plotlessness suddenly makes much more sense. Dramatically, there is no problem or tension in the ballet that demands resolution. But the Golden Age was like this, without war, famine, tension, problems of any kind, an era of innocence. Thus, it makes sense that Apollo simply is born, meets the muses, and instructs them in their respective arts. In this setting no dramatic problem is necessary, in fact, the presence of one would make no sense at all.

What are the lessons for creators here? Most artists are in touch with their influences, the artists whose work made them into the creators they are. Apollo presents an example of how to acknowledge those influences without allowing them to predominate, nod to the chosen forebear, then change course, perhaps acknowledging a different influence. As we are all borne upon the shoulders of those who came before us, and consuming art in our chosen medium means awareness of how others have succeeded in ways in which we would like to succeed, this is crucial. The invocation of Bach, Bellini and Delibes, the closeness of their artistic spirits, helps to make Apollo an artistic triumph, turning it into one of the most exceptional achievements of Stravinsky’s career, amid one of his own golden ages.